First off, I’ve experienced the #MTBoS as a very welcoming place. Its certainly very white, but I’m used to that. At three I moved to an entirely white neighborhood, was the only black student in my class through 5 years of elementary school, and I went to primarily white MS, HS and Colleges (MSU, Harvard & Columbia). I can count the number of black males in my undergrad math education classes on my thumbs. When I reflect on how I made it this far, luck is the main answer. A slight turn of events could have led me to a trajectory that is out of this profession, or towards incarceration, or left me dead. A busted tail light and a cop with a mean streak could have easily ended my life because those are the values our country espouses, but I was lucky. My parents were also lucky, and wanted to risk giving their kid an education in a good school in the suburbs. Because of all this luck I became a math teacher and an assistant principal, and have become very comfortable with learning in primarily white spaces along the way.

In most of these spaces, conversations about race is avoided, or serves to further existing beliefs. When it comes up it feels like you are simultaneously on trial, the expert witness, and the lawyer presenting the case to a jury that you may need to ask for help later or just tension friends with. One day in middle school Dexter Adams was saying to a rapt audience about how his parents drove through Detroit and heard gun shots. I spend the night at my Grandma’s once a month, and I know that those sounds were probably fireworks or cars backfiring. After some deliberation, I remember deciding it wasn’t worth it to reply. It’s anxiety provoking.

It’s even more anxiety provoking in college where you’re trying to sub-consciously prove you’re not the affirmative-action case that people seem to think you are. Speaking out is a 3-ring circus. If you’re making a point or sharing your experiences, be sure to 1) get the point across, lest they miss it and go out and ruin kids lives, 2) be positive enough to ensure they won’t hate you for challenging their long-held beliefs, only to wind up a partner on a project later, and 3) be entertaining enough that they can’t exercise the privilege of checking out. It’s hard to do even if you have great teachers and classmates, which I’ve been lucky to have. It’s still hard to garner the emotional energy to have these conversations in my primarily white school now, where I swear everyone is on the same page.

https://twitter.com/crstn85/status/1055269644586704896

I was introduced to the #MTBoS through friends I had met that I wanted to keep in touch with. In posting and sharing the things that I wanted to work on, mainly PBL and PrBL, I was able to quickly find a number of people with great ideas, abundant resources and welcoming positive energy. Despite everyone’s different contexts and perspectives, everyone is willing to chip in because we are all fighting this larger, asynchronous, guerrilla war against traditional math education. Conversations about race, social justice, the whiteness present in math education have come up over time and they are handled well. When they happen, the conversations do a good job of unearthing the experiences facing us #MTBoSers, and the populations we serve, as we all navigate the systemic injustices that emerge in our classrooms. Maybe some of the conversations are successful because they result in people understanding someone else’s perspective, or further one or two people’s thinking about something. Along the way some people get upset, unfollow people, and send tweets to let everyone know they are checking out, “I came here for math, but what you’re posting now scares me…” But the conversation keeps moving forward. Forward towards giving all kids a meaningful math education sanitized of the white male privilege that has been baked in through so many years.

There is nothing wrong about saying the #MTBoS is a community that started with lots of white people. That is a result of the system that we live in. If all the math programs, and all the teacher programs are primarily white, it follows that math education twitter will also be primarily white. The danger is whether we don’t questing the role that whiteness plays in determining the culture of math that students experience. Math has been a vehicle that reproduces societal inequalities while being billed as meritocratic and immune from biases. If the #MTBoS set out on the journey of reshaping our students’ math experiences it was certainly only a matter of time before they must deal with the latent white male privilege. This is now complicated because, the #MTBoS, and math education, is primarily white.

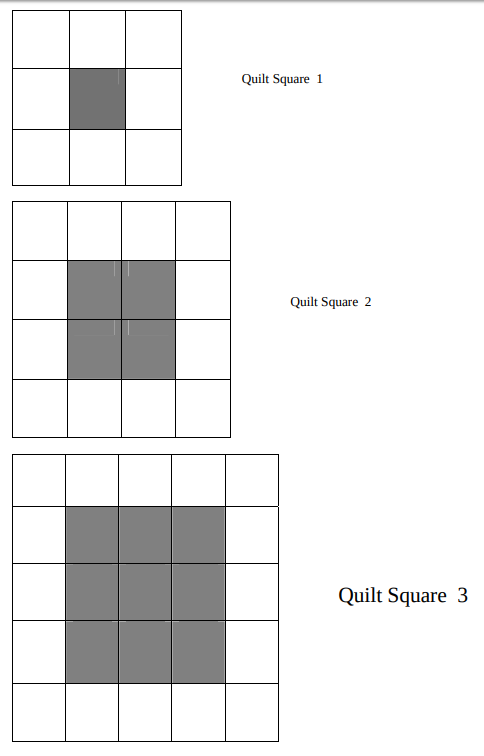

In looking at the #MTBoS’s whiteness the most important question to me is: “Can this primarily white group of math educators effectively practice anti-racism?” I don’t know the answer to that question, but I’d argue a serious consideration of this question would further the conversation than the “Why aren’t there more educators of color?” The second question is kind like asking “Why is the Canary dead?” while the first question is like asking “How do we get out of this deadly coal mine?” White Privilege is a large intractable villain that’s buried deep beneath our society like those tunnels in Stranger Things. Fighting it is going to be forever and take our whole lives, and that of our kids. Focusing on easily measured successes like the number of POC may trick people into thinking that the battle is a finite one, when it’s really an infinite one. It’s a battle that will require lots of persistence and collaboration, much like long battle that currently being waged by the #MTBoS against the traditional math system. Traditional math education is part of what is currently impeding many POC from becoming math teachers, so it is no surprise that there aren’t many who could immediately join the #MTBoS in this fight. “Can this group of mostly white kids take on this big insidious monster that no one even sees, knowing that we might not look like the people who should be facing it?” Just like in Stranger Things, it may not be the perfect team, but it may have to be the perfect team.

As someone who doesn’t participate much in conversations around race on #MTBoS or on the internet, here are three things that I think should be considered by anyone:

1) We are all from really different contexts. Conversations are happening across a number of racial, political, geographical contexts, making it difficult to provide the necessary backstory to go along with what is going on at their school.

2) The work is messy. It’s hard to know whether a social justice lesson that worked in one context won’t get you a visit to the superintendent’s office in another district. And it’s hard to know what to say when the student who beamed during that lesson divulges that they overheard the n-word in the teacher’s lounge yesterday.

3) This is people’s jobs. We are all professionals, most people’s real names and institutions are stated. Most people don’t know how to have conversations and feel like they are assured to be safe when a parent, or a student, or a superintendent might see what you’re posting.

So it’s hard to engage in a conversation that crosses many contexts, about work that is hard in nature, on a platform that poses actual risk. All of those problems get amplified when you are a person of color and talking about race in a primarily white space. Does the person reading this tweet really understand the way I experience race in my context? Am I confident that the solution I tried with my kids will work in other people’s classrooms (and not cause unintentional harm)? Am I being viewed differently than the white parties in this conversation, and could that change the way I am viewed professionally? As someone fully aware of the thin sliver of luck separating my trajectory from so many others, I worry about that luck running out every time I open my mouth.

For me personally to be involved in a conversation about race I’d need 3 things. The number 2 thing I need is what I’ll call a brave space. A teacher I know shared an article with me after her school had some tough conversations about race at their school meeting. The article (which I can email) basically says that the idea of a safe space is a myth, as safety is usually preserved for the majority culture. This is more or less what a grad school program director told me as they defended a white student who offended the people of color in one of my grad classes. Race was born out of violence and it’ll probably take some violent conversations to face it, so a promise of safety could serve to stymie whatever could come out of the conversation. The 3rd thing I’d need is the same thing I’ve always gotten from #MTBoS, and that is constant support and positive energy. The likes, and the retweets of people who you might not be following yet may be the 1st thing that needs to happen. The 1st thing I need to happen is to not have my baby daughter having a 103 fever, and my other daughter not insist that I show her spiderman videos whenever my laptop is open. I’ve wanted to get on #ClearTheAir, or respond to some of the email chains that I’ve been on, but there just isn’t enough time, or at least not yet. Maybe after October.