Today I am about to get started on my Thinking Classroom experiment. I’m probably more nervous than I should be, so writing this will help. This post is to both organize my thoughts, and serve as a nice opening to a series of posts that I’ll write as this experiment unfolds. Today I am going to talk about what I’m going to try, but first I’ll recap how exactly this experiment came to be in the first place.

How this came to be

I was at the NCTM Regional in Kansas City, heading to an early morning shift at the #MTBOS booth, when the security guard informed me that the vendor area was closed. Naturally, I checked twitter, and saw a few tweets coming from a Peter Liljedahl session, so I headed over there to catch a little bit of the end. I proceeded to have my mind blown. Turns out the Thinking Classroom had dozens of great ideas behind it, and not just by the VNPS stuff:

@pgliljedahl Problem solving is what you do when you don’t know what to do. If you know what to do it’s exercising. A good problem is a problem where there is thinking left to do. #NCTMRegionals

— Carl Oliver (@carloliwitter) November 3, 2018

@pgliljedahl When classes are too organized kids don’t really engage in thinking. Kids placed in a box keep their thinking in a box.

What's the least amount of chaos you can add?. Defront the room. Have no discernable front and face kids in all sorts of different #NCTMRegionals— Carl Oliver (@carloliwitter) November 3, 2018

@pgliljedahl With notes 63% don’t keep up or don’t do it, 90 percent don’t use it later. Students don't know why they are doing it. Tell them

Write letter to your future, dumber, self about what you learned.

Kids will need help structuring this. #NCTMRegionals

— Carl Oliver (@carloliwitter) November 3, 2018

Having a classroom built around thinking was my plan for years! 3 years ago, I stopped calling my classes algebra and started calling them Mathematical Thinking, to signal that this is going to be a different experience. Liljedahl’s research laid out a 10 point plan for making the class into the experience that I hoped to create, with research and charts to back it all up. The biggest headline of the 10 point plan was the Vertical Non-Permanent Surfaces, which I had piloted last year. The session gave me some ideas about notes, assessment, and how the teacher provides more problems for the students as the class progresses.

After the talk, I headed back to the booth and talked with Joel Bezaire who had also done some Thinking Classroom stuff in his school. He made it seem really realistic. He told me about Dry Erase Contact Paper, the kinds of problems he uses, the spreadsheet that randomizes kids, and some of the blog posts he used. He also helped me think of ways to make it work at my school, which is not traditional and I don’t have as much time with my kids who all have really different abilities. In another stroke of luck, Peter Liljedahl was doing a session around the corner at the infinity bar after I finished talking to Joel. He was super nice and answered my questions until well over his allotted time. I also was able to download a lot Dylan Kane’s Blog Posts about the thinking classroom before my plane home took to read on the flight home. The fact that all these stars aligned made it clear that the universe wanted me to try the thinking classroom this cycle.

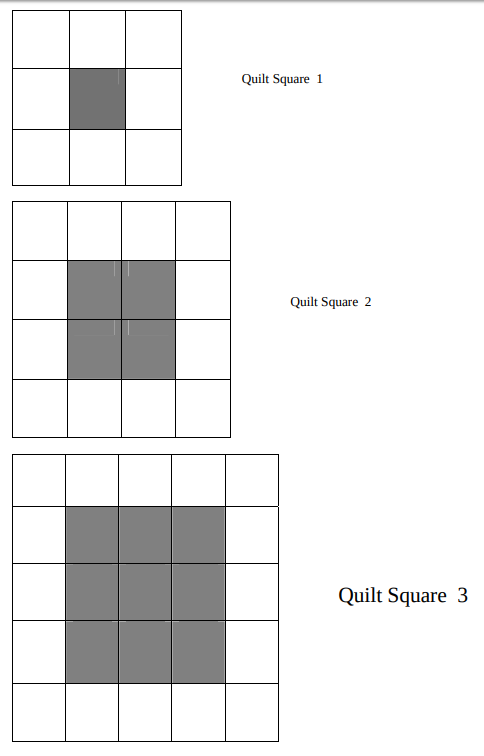

Fast forward to this morning. Things seem pretty much set. First off I have students! 11 students signed up for my class for this cycle, and a few more will trickle in which is good. This means getting kids into groups won’t be too hard, and I can save some of the whiteboard paper I would have used for a class of 30. As each kid signed up I showed them this video from Alex Overwijk, and explained some big ideas. “We’re going to do group work, and we’re not doing a whole bunch of worksheets. Instead, we’re going to maximize how much time you spend in class thinking…” Once class actually starts, I’ll need to reiterate the main ethos of what the class is, while also getting them immediately working. In the past I usually started class with a speech about me, my syllabus and how great our time together will be, but this is always boring and dry. Instead I’m going to explain a little bit about what we are doing, use the randomizer, and then get into some visual patterns and some function notation.

_______________________________

Update: I taught the first class and it was pretty interesting. The class was small in number with 4 kids of 11 kids (there was really bad weather last night, so it’s possible that people couldn’t make it in). The small class size could have been a good thing since it lowered the chances for a wide scale revolt. I made this randomizer that is basically the one Joel Bezaire described, with some modifications for my small class size, unpredictable attendance. The scary thing that comes along with small class size is the lack of different kinds of thinking. What if the small groups only come up with a couple of answers? Today the class all went through the visual patterns and came up with a few different ways to solve it. In the future, it will be hard to ensure that all of the different kinds of thinking that need to be elicited will actually show up. Maybe I’ll have to write up imaginary group work and post it somewhere else in the room as a “shadow group.”

The math wasn’t that substantial today, but we did plow through it. All the kids say they liked it and thought it was a fun. I am not clear on how we will introduce precise mathematical vocabulary and notation. Function notation will be the first thing we’ll see how it goes. Maybe I can just roll it out!